- Joined

- Dec 9, 2004

- Messages

- 42,755

- Reaction score

- 35,619

- Points

- 113

- Location

- Wandering, but not lost

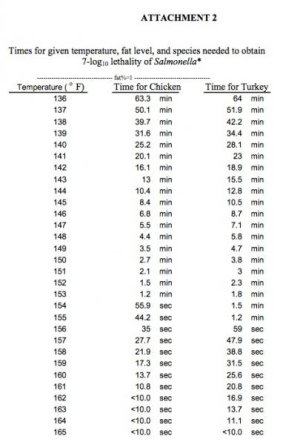

Nobody mentioned the skin (or I missed it). I assume you'd be cooking on a 300+ grill and crisping the skin?

If you listen to the podcast it makes more sense. If I'm not mistaken that's what he does with his comp chicken. And as we all know, he wins a lot in chicken.

I did listen to it and he never talks about his process. He mentiones that he cooks the whole KCBS comp on one WSM, so it doesn't sound like he has a grill available.

He also says that he cooks a breast to 145 then wraps it in foil and lets it sit. That's not the same as holding it at 145.